Near-far

(2023 - ongoing)

For a long time, I found conviction in Descartes’ understanding of vision in Dioptrique: he treated seeing as a mechanical process: light refracts, images form, and clarity emerges. He spoke of precision, correction, and sharpness. Yet as we grow older, our eyes begin to tire, and distant things become harder to grasp. What we see, does it truly exist? Perhaps vision has never been purely optical; it also carries memory, sensation, and even imagination.

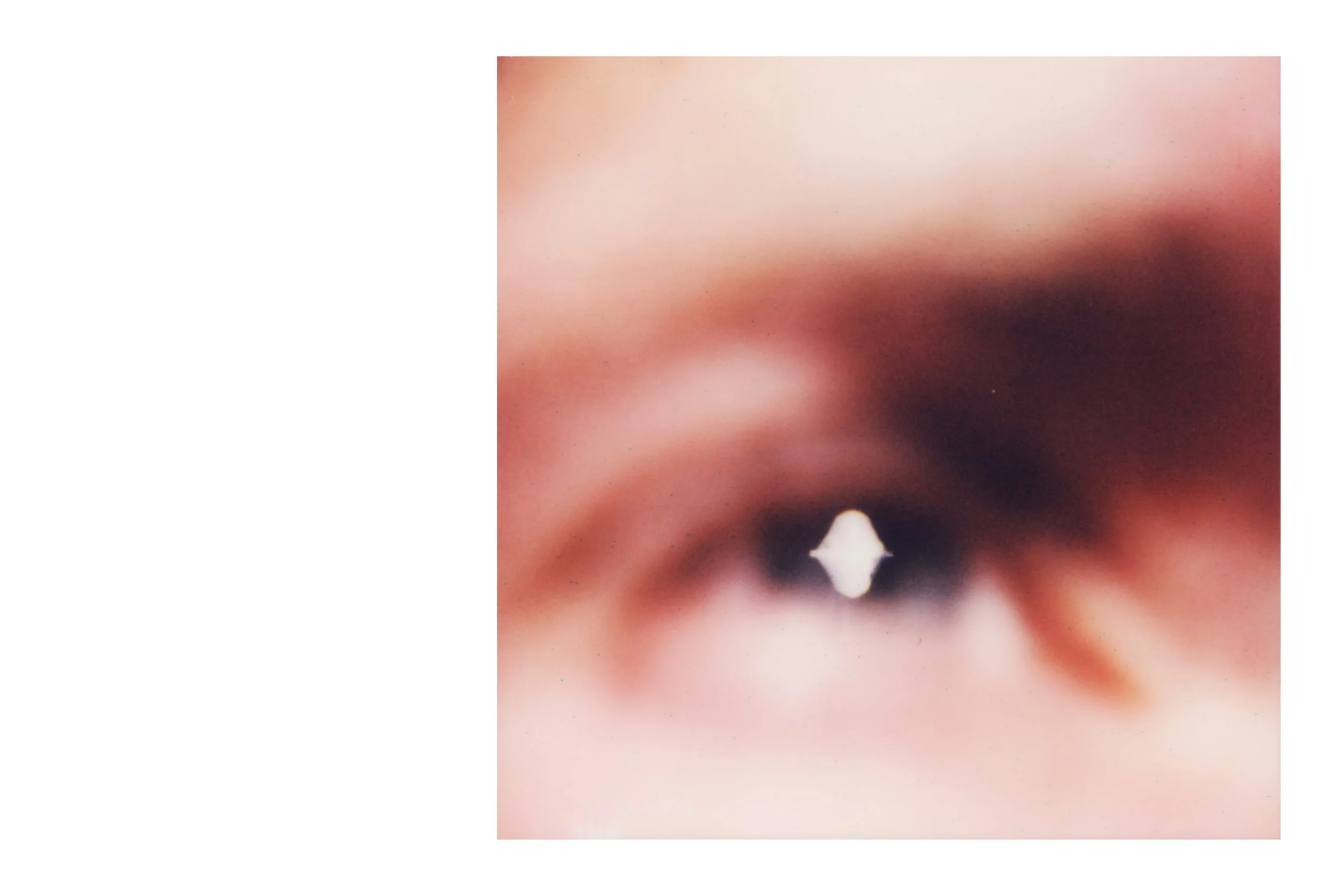

Once, I accidentally injured my left cornea, and for more than two weeks I could not open my eyes. To ease the pain, I had to keep them closed for most of the time, rendering my glasses useless. Nearsighted as I was, the world turned blurry again, reduced to shifting patches of color and interlacing light and shadow. Even after recovery, that peculiar visual experience lingered in my memory, prompting me to reconsider not only the condition of my eyes, but what seeing truly means.

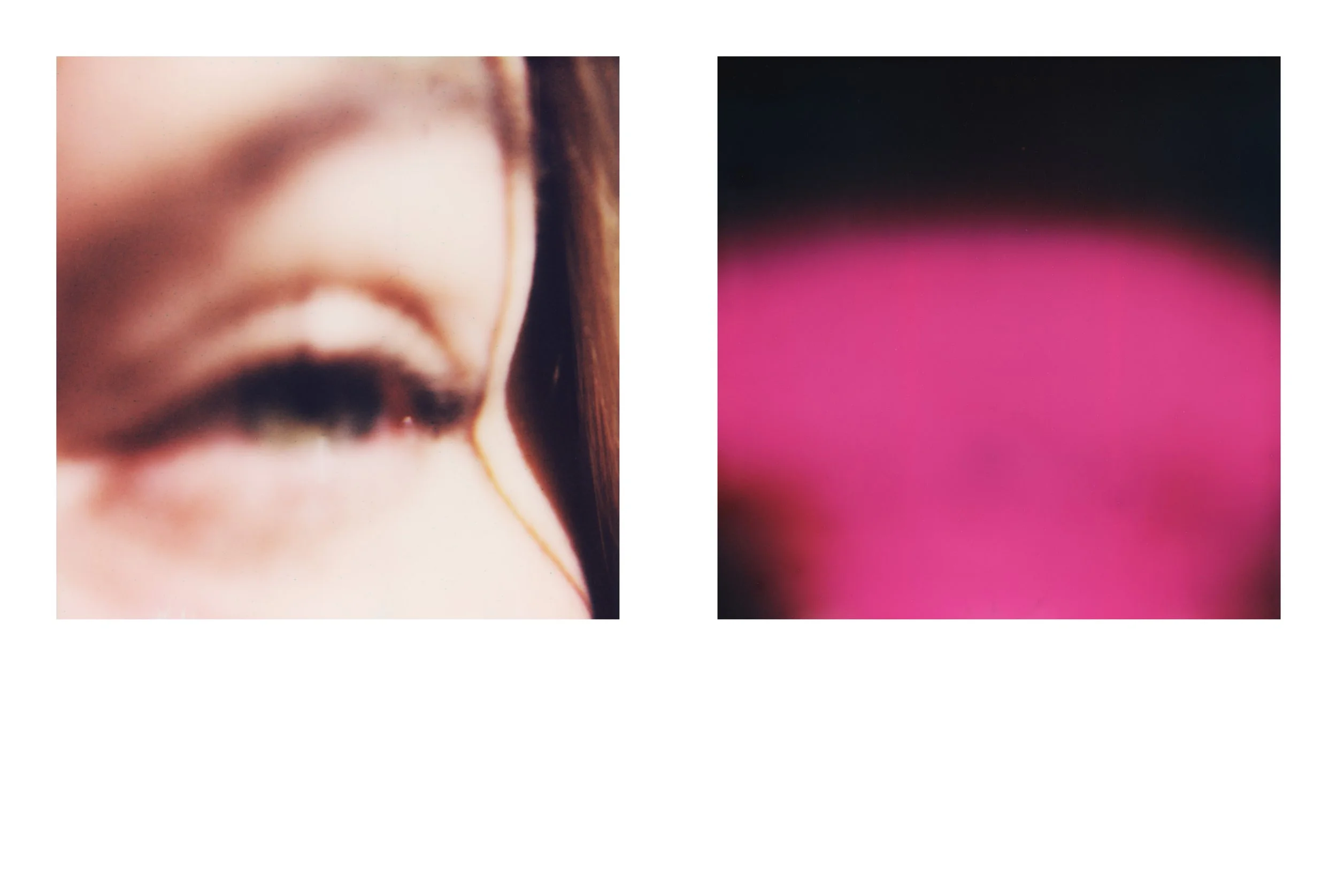

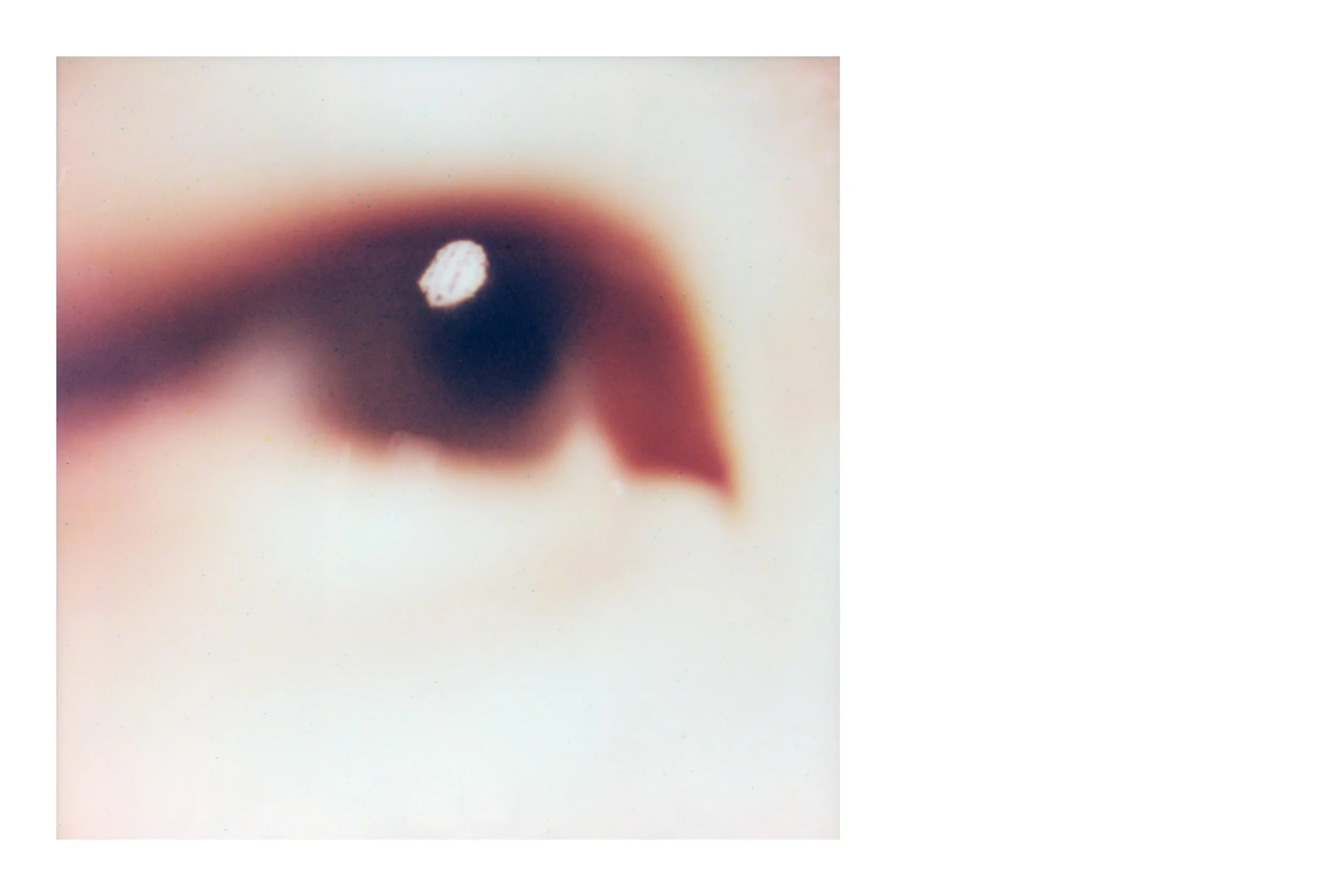

We often think of vision as something reliable, a clear window through which we connect with the world. Yet during that period, when I leaned close to the mirror trying to see my own eyes, I could never bring them into focus. It was then I realized that seeing could also be blurred and fragile. As Merleau-Ponty wrote, “The enigma derives from the fact that my body simultaneously sees and is seen. That which looks at all things can also look at itself and recognize, in what it sees, the ‘other side’ of its power of looking.” My eyes were both seeing and being seen, yet nothing felt truly in focus.

That blurred vision was not merely an obstacle. It felt like another way, perhaps a more essential way, of sensing the world. Merleau-Ponty reminds us that vision is not just about passively receiving images, but about how we move, how we inhabit space, and how our bodies shape what we perceive. In those moments, seeing was no longer simply looking; it was also feeling, remembering, and imagining what lies beyond the haze.

This led me to think of the old Polaroid camera I keep by my side. As the machine aged, its images grew increasingly unpredictable, until each development felt like a small act of divination. Rather than faithfully reproducing what was in front of it, the camera seemed to interpret the moment on its own terms, capturing the resonance between myself and the person I was photographing. I began inviting friends to join me in this peculiar ritual of chance, and together we created these Polaroid images.

They drift between states of focus and dissolution, nearness and distance, presence and disappearance, red and blue. Again and again, I find myself returning to the question: what does it truly mean to see? And how much of what we perceive is shaped not by our eyes, but by the depths within us: our long-held sensations, memories, and the echoes they leave behind? It could be near, and still far.

在很长的一段时间里,我深信笛卡尔在《屈光学》中对视觉的理解。他把看见当作一种机械过程:光线折射、图像成形、视野得以清晰。他谈论的是明晰、校正与精准。但随着年龄增长,我们的眼睛渐渐变得疲弱,较远的事物也越来越难以捕捉,我们所看到的,真的存在吗?也许视觉从来不只是光学,它也承载着记忆、感受,甚至想象。

有一次,我的左眼角膜意外受伤,在那两个多星期里,我无法睁开双眼。为了缓解疼痛,我只能长时间地闭着眼睛,眼镜自然也派不上用场。原本近视的我,世界又重新变得模糊不清,只剩一片片游移的色块与光影交错。这段特殊的视觉经验,即便在康复之后,依然留在我的记忆里,也促使我重新去思考,不只是眼睛本身的问题,更是“看”究竟意味着什么。

我们总以为视觉可靠,是与世界沟通的清晰窗口。但在那段时间里,我常常凑近镜子,试图看清自己的眼睛,却始终无法让视线聚焦。那一刻我真正意识到,看,其实也可以是模糊的、脆弱的。正如梅洛-庞蒂所写道:“奥秘在于,我的身体既是看者,也是被看者。那个注视万物的眼睛,也可以看向自己,并在所见之中认出它凝视能力的‘另一面’。”那时,我的眼睛既在看,也被看着,但一切却始终无法真正入焦。

那种模糊的视野,并不只是障碍,它反倒像是开启了另一种感知方式,甚至可能才是最贴近本质的一种方式。梅洛-庞蒂提醒我们,视觉不只是被动地接收图像,它关乎我们如何移动、如何与空间共存、身体又如何形塑我们眼中的世界。那时的“看”,已经不仅仅是注视,它也包含了感受、回忆,还有对朦胧背后事物的想象。

这也让我想到了身边那台有着一定岁数的老式宝丽来相机。随着机身的老化,它的成像慢慢趋于不可预测,以至于每次的显影都有点像占卜仪式:与其说它再现被拍摄的物体,倒不如说更多的是以它的喜好来捕捉和呈现我与被摄者的同频共振。于是我邀请身边的朋友来和我一起合作参与到这种特殊的占卜中,最终得到了这些宝丽来图像。

它们在这些状态之间游走:聚焦与消散、临近与遥远、呈现与隐匿、红霞与蓝夜。这又让我反复地思考,“看见”究竟意味着什么?而我们所见,又有多少并非由眼睛决定,而是由我们内心深处、那些怀揣已久的感知与记忆所构成?有时,它是那样近,却又似乎始终在远方。